Key Points

- Governor Signed Most Fiscal Bills. Governor Newsom signed 71 percent of the policy bills that passed through the Senate Appropriations Suspense process.

- Potentially $2.9 Billion in New General Fund Costs. Signed bills could generate between $422 million and $2.9 billion in new General Fund costs, though the highest cost bills depend on future legislative or voter actions.

- New Costs Could Increase Annual Deficits. The state is already on the verge of annual deficits beginning in 2020-21, and the new policy bill costs create fiscal pressure that could require use of reserves or budget cuts.

When it comes to state spending, the annual budget appropriately receives most of the attention. However, hundreds of policy bills that pass each year can create significant new spending as well. In order to assess how policy bills affect state spending, we estimated the costs of bills that were placed on the Senate Appropriations Committee’s “Suspense” file[1] before eventually passing on to be signed or vetoed by Governor Newsom. This analysis provides an idea of how the potential costs of policy legislation will affect the budget moving forward. For bills enacted in 2019, our review shows that General Fund spending through new legislation would range from $422 million to more than $2.9 billion.

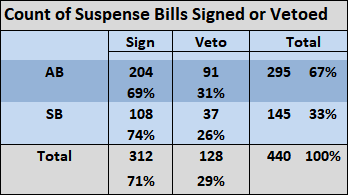

Governor Signed Most Suspense Bills. The two Appropriations Suspense hearings, held in May for Senate bills (SBs) and August for Assembly bills (ABs), resulted in 623 bills passing on for a vote by the entire Senate. As summarized in the table on the next page, the Legislature eventually passed 440 of these bills on to the Governor, including 295 ABs and 145 SBs. The Governor signed 312 (71 percent) and vetoed 128 (29 percent) of these bills.

While each house saw a significant majority of its Suspense bills signed, Governor Newsom signed a slightly higher percentage of Senate bills (74 percent) compared to Assembly bills (69 percent). In comparison, the Governor signed 870 bills overall out of 1,042 that reached his desk in 2019, including fiscal and non-fiscal bills, a signing rate of 83 percent.[2] This indicates a somewhat lower signing rate for fiscal bills compared to the overall bill universe. The Governor’s veto messages for fiscal bills frequently referenced costs as a factor in his decision.

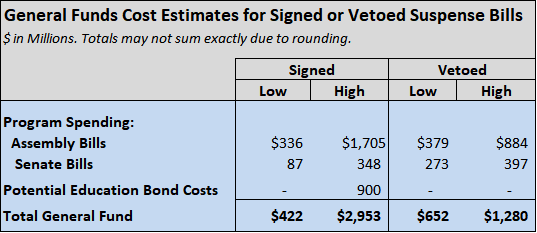

Potentially $2.9 Billion in New State Costs. We project that the combined General Fund costs for signed bills would range from about $422 million to $2.9 billion, once the bills are fully implemented,[3] as summarized in the table on the next page. However, up to $1 billion of these potential costs depend on a future appropriation by the Legislature, and another $900 million in annual costs require voter approval of a bond measure for education in 2020. These contingencies add to the uncertainty of the overall fiscal effects.

The Governor vetoed bills with General Fund costs ranging from $652 million to nearly $1.3 billion per year. The highest-impact General Fund bills signed or vetoed are summarized on the next page.

Signed General Fund Bills

- AB 38 (Wood): Costs would result to provide funds to create fire-resistant homes, businesses, and public properties. The new program created by the bill is contingent upon a future appropriation by the Legislature. Since an earlier version of the bill included a $1 billion General Fund appropriation, we listed the costs as potentially ranging from $1 million to $1 billion.

- AB 48 (O’Donnell): Contingent on voter approval in 2020, costs would gradually increase to potentially $900 million per year for debt service on a $15 billion bond measure for education and higher education.

- AB 32 (Bonta): Costs of potentially $134 million per year would result from the prohibition on using private, for-profit prisons, which typically cost less than state facilities, to house some state inmates (with certain exceptions).

Vetoed General Fund Bills

- SB 5 (Beall): Would have created costs of up to $250 million annually over a period of nine years to fund certain housing projects. The Governor’s veto message cited the bill’s cumulative potential cost of $2 billion as a key reason for the veto.

- AB 197 (Weber): Would have created costs potentially in the hundreds of millions annually to require all elementary schools to offer at least one full-day kindergarten program. (Our analysis assumed an upper range of $200 million annually.)

- AB 500 (Gonzalez): Would have created costs of up to $163 million per year or more to provide six weeks of maternity leave to employees of K-12 schools and community colleges. The Governor’s veto message cited costs as a concern and stated the spending should be considered through the budget process.

- SB 349 (Portantino): Would have reduced tax revenues by $340 million per year by lowering the minimum franchise tax for businesses with sales less than $15 million per year. (Since this effect is a revenue decrease, rather than a spending increase, it was not included in the total spending estimate provided above.)

Policy Legislation Costs Could Help Generate Deficits. To put the potential $2.9 billion in General Fund spending from new policy legislation in context, the 2019 Budget Act authorized spending of nearly $148 billion General Fund. Overall reserves totaled $19 billion, which included a discretionary reserve of about $1.4 billion and a constitutionally protected reserve of $16.5 billion (sometimes referred to as the Rainy Day Fund).

At the time the Governor signed the budget in June, the Department of Finance projected annual operating surpluses of only $33 million or less for each of the next three fiscal years beginning in July 2020. In other words, the three years following the current year are already projected to barely break even on a year-to-year basis, despite record-high revenues. These projections also dubiously assumed that the state would cut spending by $1.7 billion annually beginning in January 2022 due to “trigger” provisions that the budget already authorized.[4] These spending cuts would take effect if the Governor’s Department of Finance projects that revenues appear insufficient to meet existing spending requirements at that time.

With such a precarious outlook for annual spending, the costs of newly signed policy legislation could potentially increase operating deficits in the next few years or require additional use of reserves, depending on how quickly costs ramp up and other contingencies. Presumably, for example, the Legislature would not fund the AB 38 fire prevention program at a $1 billion level if revenues appear to be falling. Instead, the program could be funded at a lower level or delayed entirely. In addition, higher spending created by policy bills could increase the chance that the budget “trigger” cuts would go into effect.

Overall, irrespective of the merits of some policy bills, 2019 once again saw a substantial amount of potential General Fund spending approved that will complicate the state’s budget picture moving forward.

Download (pdf)

[1] A bill referred to the Senate Appropriations Committee is typically placed on the “Suspense” file at its initial hearing if it is likely to cost more than $50,000 from the General Fund or $150,000 from special funds in a single year. The Committee later holds a Suspense hearing at which some of these bills are passed to the full Senate.

[3] The ramp-up period for the bills could differ substantially; in some cases, costs will occur in 2020, but in other cases, it may take several years for costs to reach the full implementation level. Also, bills with costs lower than $1 million per year were excluded from the spending estimates since these bills in aggregate typically account for less than 10 percent of total spending. Forecasting the costs of legislation is imprecise by nature, and thus these estimates should be viewed as a general scope of potential costs.